Hercules’ Club Tree

Unique Trees of North Texas:

Hercules’ Club

(Zanthoxylum clava-herculis)

By Jeremy Priest

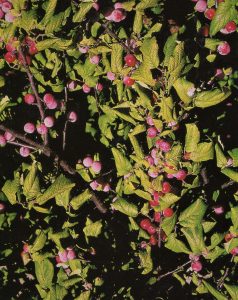

This aptly name tree certainly deserves a spot on the “unique” list. Hercules’ club, which is also known as toothache tree, tickle tongue, pepperbark, or prickly ash, is part of the Zanthoxylum genus. The genus has many species with overlapping or similar common names, but only 3 other Zanthoxylum species grow in Texas (Texas Hercules’ club, lime pricklyash, and tickletongue). Many of the common names associated with this species refer to the stimulating nature of the bark and wood of the tree. The tree was historically used by Native Americans and early settlers to numb the mouth, hence the name toothache tree. The name Hercules’ club is easily noticed in the scientific name and fits the appearance of large specimens. When young, the tree develops sharp spines on the bark (not just at leaf nodes as with some other species) which are usually distributed throughout the trunk and branches. As the tree ages, the prickles develop corky, pyramidal bases and eventually lose their sharpness. These corky structures may eventually develop strong ridges as seen below. No matter the age, the trunk of this tree always looks like it could be fashioned into a fearsome weapon.

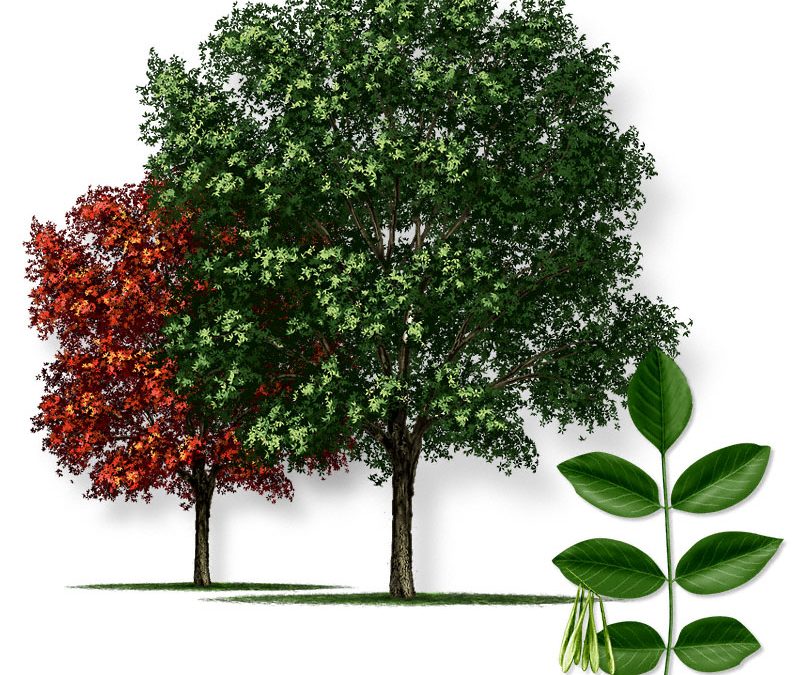

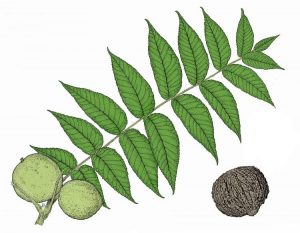

To identify Hercules’ club look for the distinct spines on the trunk and branches and pinnately compound leaves. Typically 5-19 leaflets, including a terminal leaflet, that are 0.5-4.5 inches long. Small greenish white flowers form in the spring at the tip of branches and seeds are shiny black but not very conspicuous. Don’t confuse Hercules’ club with devil’s walkingstick (Aralia spinosa), which grows straight up with very little branching and has doubly compound leaves. While the leaves may be similar to other compound leaved understory species such as sumac, or the spines similar to species such as honey locust, Hercules’ club is quite distinct and easily distinguished from all except other members of Zanthoxylum. Texas Hercules’ club is more common farther south and west and is a smaller stature tree with only 3-7 leaflets (5 is typical) 0.5-1.5 inch long with the entire leaf less than 4 inches long. Texas Hercules’ club also does not develop the strong corky bases on older prickles. The national champion Texas Hercules’ Club is in North Richland Hills with a height of 22 feet and a spread of 20 feet.

Hercules’ club is an understory tree that typically grows to less than 20 feet in height; however, it is only moderately shade tolerant and relies on establishing with limited competition. The seeds are popular with birds and remain viable after being eaten allowing the species to spread profusely along fencerows and transition zones. Another way it establishes with limited competition for light is to grow on poor sites such as upland, dry, or very sandy areas. In the Cross Timbers region, the overstory on these sites often consists of post oak and blackjack oak. As the tree is adapted to grow on harsh sites with low overall plant density, developing spines reduce wildlife browsing and helps Hercules’ club outcompete other vegetation. If the tree is to be planted, select a relatively dry area with good sunlight. Also remember that the spines on the trunk can be a concern but can be removed or the tips cut if needed. The sharp spines usually do not grow back as the bark develops.

Hercules’ club is native throughout the southeastern US extending from Florida to central Texas. It is tolerant of acidic and alkaline soils. This species also prefers well-drained or sandy soils and does not tolerate flooding. Some of the largest Hercules’ club in Arlington are found at the Southwest Nature Preserve, which is known for being a dry, upland site with some unusual species. There may also be Texas Hercules’ club at the nature preserve as some of the trees develop drastically different bark texture and smaller leaves. Another Arlington park where Hercules’ club is prevalent is Cliff Nelson, which has similar site conditions to the Southwest Nature Preserve. Fully grown the tree may reach 20 feet in height and 15-20 feet in crown diameter, with a trunk diameter of 8-12 inches in 30-40 years. Given the poor sites on which these trees are found they do grow somewhat quickly, as much as 1 foot per year in height. The largest Hercules’ club reported in Texas is in Nacogdoches County (East Texas) and has a height of 38 feet and a trunk diameter of nearly 20 inches, although trees in the Cross Timbers would not likely grow this large.

Sources

Vines, R. A. (1982). Trees of north Texas (Vol. 14). University of Texas Press.