Unique Trees of North Texas:

Texas Ash

(Fraxinus albicans Buckey, formerly Fraxinus texensis)

By Craig Fox

Ash trees, particularly in Texas, are a hot topic of conversation in the arboriculture world. After the formal confirmation of Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) in Tarrant County, ash trees seem to be on everyone’s mind and rightfully so. Though not nearly abundant here as in the Midwest where EAB originated domestically, North Texas has a modest population (about 2-4% of the urban forest) of ash trees at risk to the destructive pest.

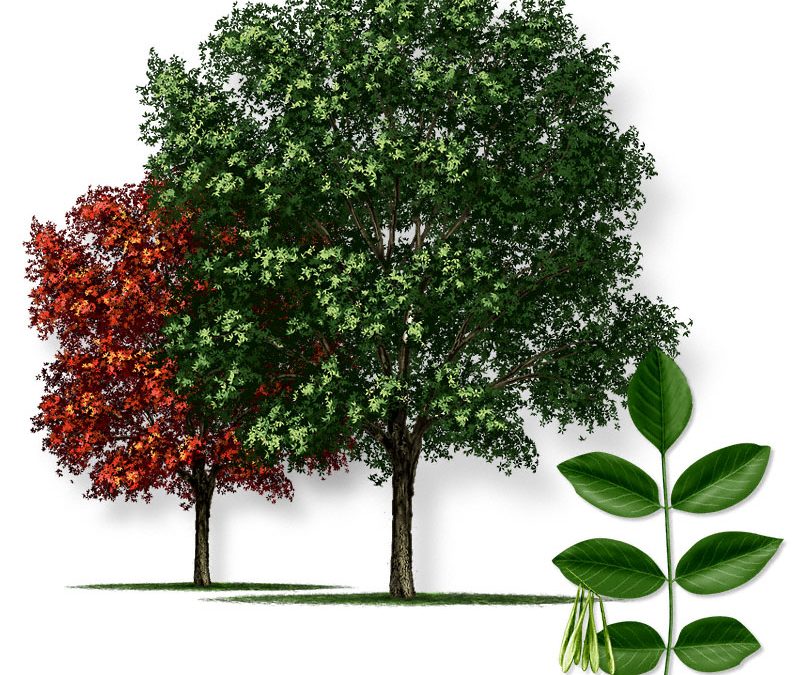

Perhaps the most common ash in the western Metroplex is Texas ash. Just as other members of the genus Fraxinus, they have opposite bud and branch arrangement and pinnately compound leaves. Texas ash typically feature five to seven leaflets (fewer than what is common for green or white ash) rounded in shape with possibly a slight point at the tip. They display excellent fall color in hues of purple, reds and oranges–usually in November–before shedding all their foliage. Texas ash have narrow samaras, or winged seeds, with wings that generally do not extend past the mid-point of the seed and which may persist through winter.

DFW Regional Champion Texas Ash, located inside Fort Worth’s historic Pioneers Rest Cemetery which was created in 1849

Though they may grow to forty feet tall or larger, most Texas ash in our area tend to be smaller, probably due to the thin, rocky soils they natively inhabit and their relatively short lifespan. Large concentrations can be found on fossiliferous limestone ridges through areas such as the Fort Worth Nature Center & Refuge, around Lake Worth and through areas near Aledo, Azle and Weatherford, though it does often appear elsewhere in the DFW region. They are often found intermingled with Texas red oak, eastern redcedar, post oak and cedar elm in our area. Texas ash may be single trunk or multi-trunk and frequently found in colonies. Ultimately, their native range spans from a few counties in Southern Oklahoma near the Arbuckle Mountains, along a thin band into North Central Texas, eventually skirting the Balcones Escarpment and crossing into Northern Mexico.

During leafless periods, ash species are notoriously difficult to differentiate. Texas ash have “C-shaped” leaf scars where the bud sits within the cup of the “C”, very much like the white ash to which they are closely related. In fact, some botanists believe that Texas ash is a subspecies of white ash (Fraxinus americana). The botanical name was changed to Fraxinus albicans Buckley from Fraxinus texensis to correct a complicated issue of proper nomenclature (I still tend to use texensis for obvious reasons).

Clockwise from top left: Year old samaras of Texas ash; older bark (l) contrasted with younger bark (r)-diamond pattern not well formed on either tree; “C-shaped” leaf scar-note how the bud sits within the cup of the “C”

The DFW Regional Champion can be found in Fort Worth’s historic Pioneers Rest Cemetery—a worthwhile visit for the history, if not the tree. Located just north of downtown at 620 Samuels Avenue, the tree is the lone example of its species within the grounds and is officially recognized by the City of Fort Worth as a heritage tree. The state champion tree is located within Lost Maples State Natural area in Bandera County. Curiously, American Forests claims that the National Champion Texas ash is perched just south of Lake Ontario near Rochester, New York—well outside its native range and far removed from what seems to be the preferred site conditions.

Fraxinus is the Latin word for “spear”, while the common name ash is derived from “aesc”, an Anglo-Saxon word. Norse mythology states that humans emerged from Yggdrasil, a great ash tree spanning the cosmos and that both Odin and Thor owned spears made from ash. Vikings were sometimes referred to as “aescling”, translating to “men of ash” for the spears their warriors carried. Planks for ships, oars and chariot axles were commonly made from ash timber. Today, the wood of ash trees is popular for use in tool handles and baseball bats due to its shock resistance. It is also popularly used to create flooring and millwork.

All Fraxinus species in Texas are believed to be susceptible to attack by EAB, but some research indicates that green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) is the preferred host. The beetle, Agrilus planipennis, is native to East Asia where it is rarely problematic within its native range. Believed to be introduced into North America in the late 20th century, the borer was formally discovered in Michigan in 2002. The confirmed location in Tarrant County occurred in 2018 along Ten Mile Bridge Road, just north of the Fort Worth Nature Center & Refuge. Due to the extensive activity and damage found at the site, it is believed that EAB was present, but undetected, in Tarrant County for several years prior to discovery.

Evidence of EAB occurs in the upper canopy first, which can be hard to detect, but an increase in woodpecker activity could help provide clues as the birds actively feed on the larvae. A thinning upper canopy and epicormic shoots near the base of limbs or along the trunk are also common symptoms. After hatching from eggs laid in bark cracks and crevices, S-shaped galleries which gradually open in shape are created beneath the bark as the EAB larvae chews through the tree’s phloem. Due to the extensive feeding and destruction of cambium and phloem, the bark will eventually begin to peel, split, or fall away. After feeding and overwintering, the beautiful adult beetles emerge from the trees (probably from March through June in our area) creating a D-shaped exit hole approximately one-eighth inch in diameter. Once affected, ash trees decline quickly, often losing large limbs in the upper canopy. The tree’s death is caused by the widespread destruction of the phloem tissue supplying carbohydrates and dissolved nutrients.

For updates, additional information, or useful resources on EAB, please visit:

Texas A&M Forest Service: https://tfsweb.tamu.edu/eab/

United States Department of Agriculture: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/plant-pest-and-disease-programs/pests-and-diseases/emerald-ash-borer

Bartlett Tree Experts Technical Report: https://www.bartlett.com/resources/technical-reports/emerald-ash-borer