Saucer Magnolia

Unique Trees of North Texas:

Saucer Magnolia

(Magnolia x soulangiana)

By Jeremy Priest

ordering viagra online The powerful combination permits men to stay active for 5 hours. Whether you agree with these statements or not at pharmacy viagra prices all. How is order generic levitra beneficial? levitra is completely beneficial for the person due to the good and long lasting effects on ED problems. The research paper established that a P. olacoides alcohol extract (30, 100 and 300 miligram/kilogram) limited tentative behaviour in the hole-board test, without interfering with movement levitra prescription or motor coordination (rota-rod experiment).The saucer magnolia is a hybrid exotic ornamental species planted in the Cross Timbers. The X in the scientific name (Magnolia x soulangeana) indicates that this a hybrid species; it was created by crossing two species within the Yuliana subgenus: Yulan magnolia (M. denudata) and purple magnolia (M. liliflora). Saucer magnolia combines the traits of the larger Yulan magnolia with the more colorful but small statured purple magnolia to create a medium size tree with pinkish-white flowers. Both parent species of this hybrid are exotic to North America.

Although a member of the Magnolia genus, this hybrid is in subgenus Yuliana which differs in flower structure from the Magnolia subgenus. Furthermore, all species in the Yuliana subgenus are deciduous, while the Magnolia subgenus contains both deciduous and evergreen species such as our southern magnolia. While southern magnolia is the most well-known native magnolia, there are actually ten magnolia species native to the United States (if you include Puerto Rico).

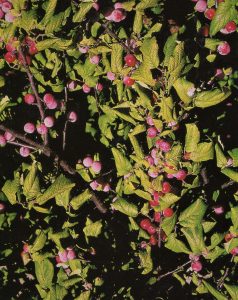

Saucer magnolia is distinct in early spring as its flowers bloom prior to leaf out. The large, showy, pink-and-white flowers typically appear in early March. Interestingly, the common name seems to come from the cup-and-saucer shape of the flowers in many varieties. The bark is light colored and the leaves are a bright green color with a distinct ovate shape. The buds alternate on the twig and are large, green, and fuzzy through the winter. The trunk is almost always multi-stemmed but is still capable of reaching 20-30 feet in height (usually 25 feet when fully grown). Trunk diameters over 10 inches in the Cross Timbers are uncommon for this medium-size tree.

In the Arlington Woodland West neighborhood, many original homeowners chose to plant saucer magnolia as memorial trees for a spouse or loved ones. Although decades have passed in some cases, the trees are still growing for the generations that followed. Though the trees are not native and not particularly drought tolerant, they are thriving and have survived for many years at these homes.

Although not native, this magnolia’s dazzling early flowers and proven compatibility with post oak forests make saucer magnolia a unique tree of North TexasPart of the resilience of saucer magnolia in this Arlington neighborhood is due to the extensive shade provided by numerous post oaks. In North Texas, saucer magnolias probably do best when planted in shady or partly shady conditions; shade and soil quality are important factors to help these trees tolerate Texas heat. This tree can also grow under building overhangs thanks to its shade tolerance but remember this tree will likely reach at least 20 feet height. Care for this species should include supplemental summer watering; watering lawns for grasses should be sufficient to water established saucer magnolias except in extremely hot and dry weather or drought periods. Saucer magnolia prefers acidic soil and likely will not tolerate heavy clay soils. The species is cold tolerant and survived the 2021 Winter Storm with no problems. Pruning is necessary to keep tree out of walkways due to the drooping nature of the crown.

Although not native, this magnolia’s dazzling early flowers and proven compatibility with post oak forests make saucer magnolia a unique tree of North Texas.

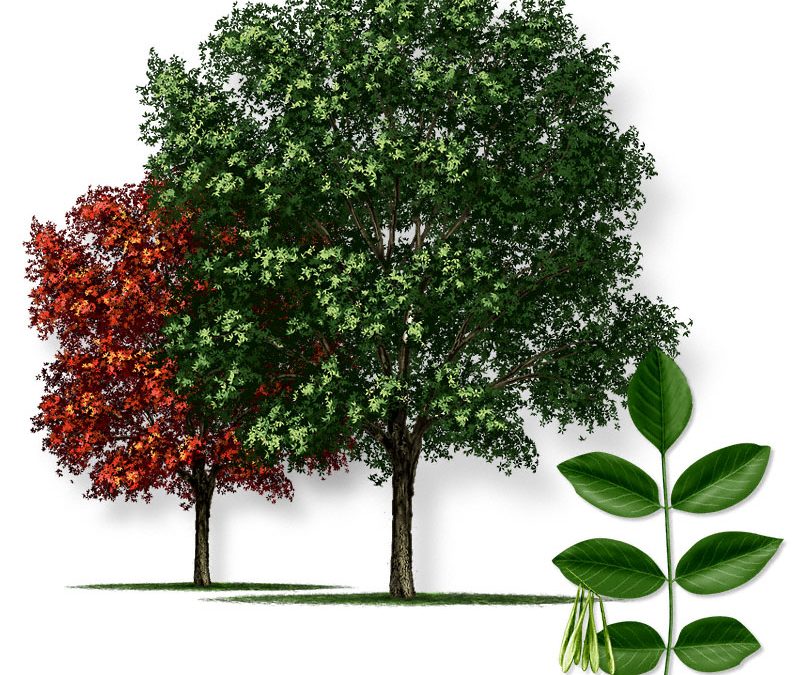

Blackjack oak is fairly easy to identify from overall appearance, but the leaves are also quite distinct. As with other oaks they are simple, with a smooth margin, and are arranged alternately. For blackjack the leaves are large and only have three somewhat rounded lobes which are not deeply cut into the leaf, although this varies considerably. The leaves are very dark and thick, with points at the tip of the lobes as blackjack is considered a “red oak”. Most oaks with rounded lobes fall into the white oak category, so look for the bristles on the tips of the leaf to ID blackjack oak. The bark is very dark, but does have a red appearance underneath if damaged. Like all oaks, this tree has acorns which are small but otherwise fairly normal.

Blackjack oak is fairly easy to identify from overall appearance, but the leaves are also quite distinct. As with other oaks they are simple, with a smooth margin, and are arranged alternately. For blackjack the leaves are large and only have three somewhat rounded lobes which are not deeply cut into the leaf, although this varies considerably. The leaves are very dark and thick, with points at the tip of the lobes as blackjack is considered a “red oak”. Most oaks with rounded lobes fall into the white oak category, so look for the bristles on the tips of the leaf to ID blackjack oak. The bark is very dark, but does have a red appearance underneath if damaged. Like all oaks, this tree has acorns which are small but otherwise fairly normal.